The Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS) marks a monumental shift in India’s criminal law, ushering in a new era of justice. With over 160 years since the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, was established, the BNS introduces a modern, inclusive, and tech-friendly legal framework to address the complexities of today’s society.

Let’s dive into the key transformations in the BNS and explore their importance in shaping the future of India’s criminal justice system.

1. Tech-Smart Laws: Finally Catching Up!

India’s digital boom brought with it a surge in cybercrimes, from data breaches to online fraud and identity theft, but the IPC was ill-equipped to address these modern threats. As technology rapidly advanced, the existing legal framework failed to keep pace, leaving gaps that criminals could exploit.

What’s New in BNS?

- Offences through electronic means are clearly recognized.

- Syncs with definitions under the IT Act, 2002 and Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023.

- Includes digital records, online threats, and cyber manipulation.

🕹️ Modern problem? Modern solution.

IPC’s Issue:

- Outdated language, no clear cyber provisions.

- Left gaps that cybercriminals could exploit.

2. Community Service: A Fresh Form of Justice

Not every offence needs a jail sentence.

What’s New in BNS?

- Community service introduced for petty crimes.

- Focus on restorative justice, not just punishment.

💡 A chance to make amends constructively, not just sit behind bars.

IPC’s Issue:

- Only imprisonment, fine, or death.

- No room for rehabilitative justice.

3. Gender Inclusivity: A Step Forward

Justice must serve everyone, and the BNS takes a significant leap toward recognizing gender diversity by acknowledging the rights and dignity of all individuals, regardless of gender identity.

This reform ensures that the legal system is more inclusive, providing better protection against discrimination and violence for gender minorities.

What’s New in BNS?

- Defines “gender” to include transgender persons (Section 2(10)).

- Offences like voyeurism made gender-neutral.

🚻 Inclusivity begins in the law.

IPC’s Issue:

- Mostly gender-specific (often male-perpetrator, female-victim).

- Did not recognize women or trans individuals as possible offenders or victims in some cases.

4. Crime-Specific Clarity: Snatching & Mob Lynching

Some crimes were too common, and too overlooked, often slipping through the cracks of outdated laws. These offences, ranging from domestic violence to cybercrimes, were either inadequately addressed or ignored entirely.

What’s New in BNS?

- Snatching gets its own definition (Section 304).

- Clear provisions against mob lynching and group violence.

👥 Because mob justice is no justice.

IPC’s Issue:

- No specific recognition of snatching (clubbed with theft).

- Vague laws that didn’t match the severity of modern crimes.

5. Goodbye to Colonial Shadows: Adultery & Sedition Out!

BNS boldly removes the dusty relics of colonial control.

What’s New in BNS?

- Adultery decriminalized, in line with the Supreme Court’s verdict.

- Sedition law omitted, though Section 152 raises eyebrows with vague language.

🔥 India’s legal system is finally breaking free from colonial influence.

IPC’s Issue:

- Retained these outdated, often misused, provisions.

Conclusion: Ushering In a New Legal Era

The Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, goes beyond merely replacing outdated laws; it stands as a reflection of India’s progress, diversity, and digital future. By eliminating archaic provisions, acknowledging modern crimes, and fostering an inclusive approach, the BNS sets the foundation for a more equitable, efficient, and future-proof legal system.

However, it’s crucial to understand that laws are only as effective as their implementation. The true impact of the BNS will be determined by how it is applied in the courts and how the judiciary interprets and enforces these new provisions.

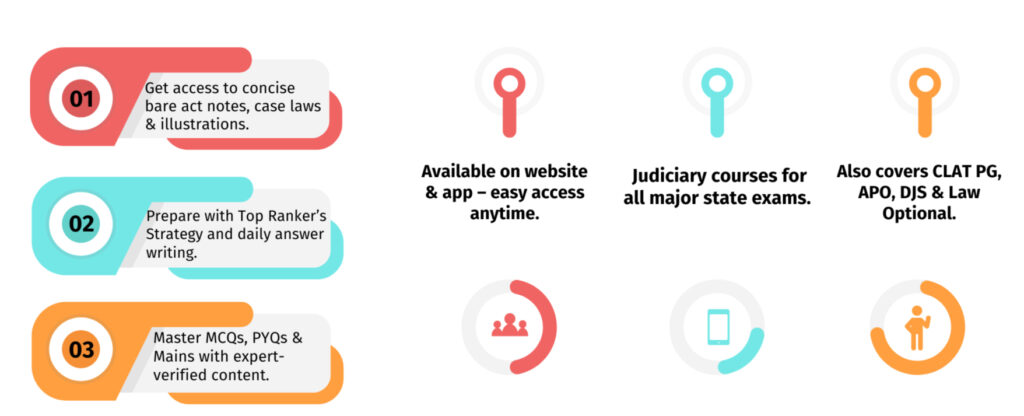

Preparing for Judiciary Exams? This Is Your Golden Moment!

Want to master every section of the BNS and understand how it compares with the IPC?

- Join thousands of aspirants learning with Edzorb Law!

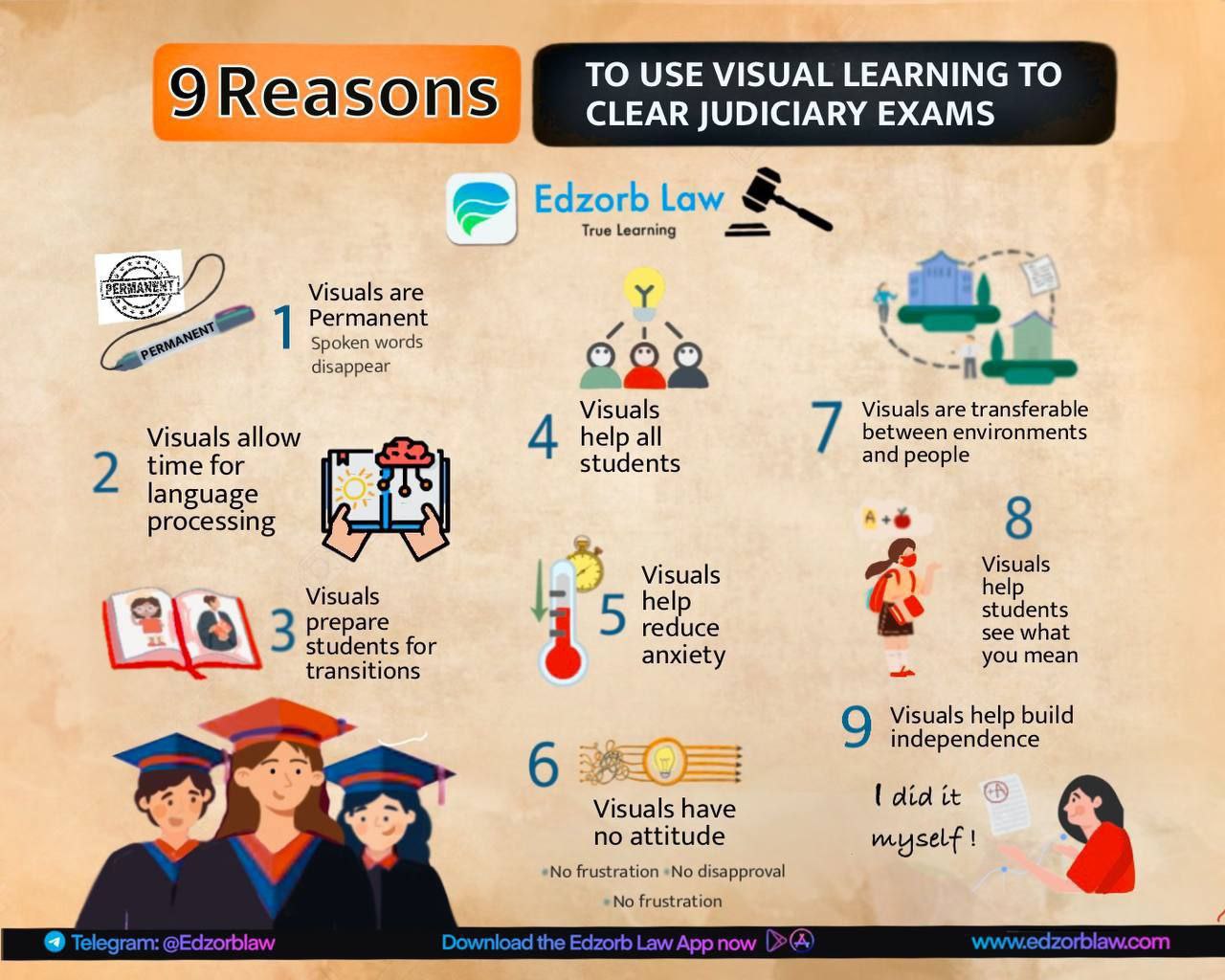

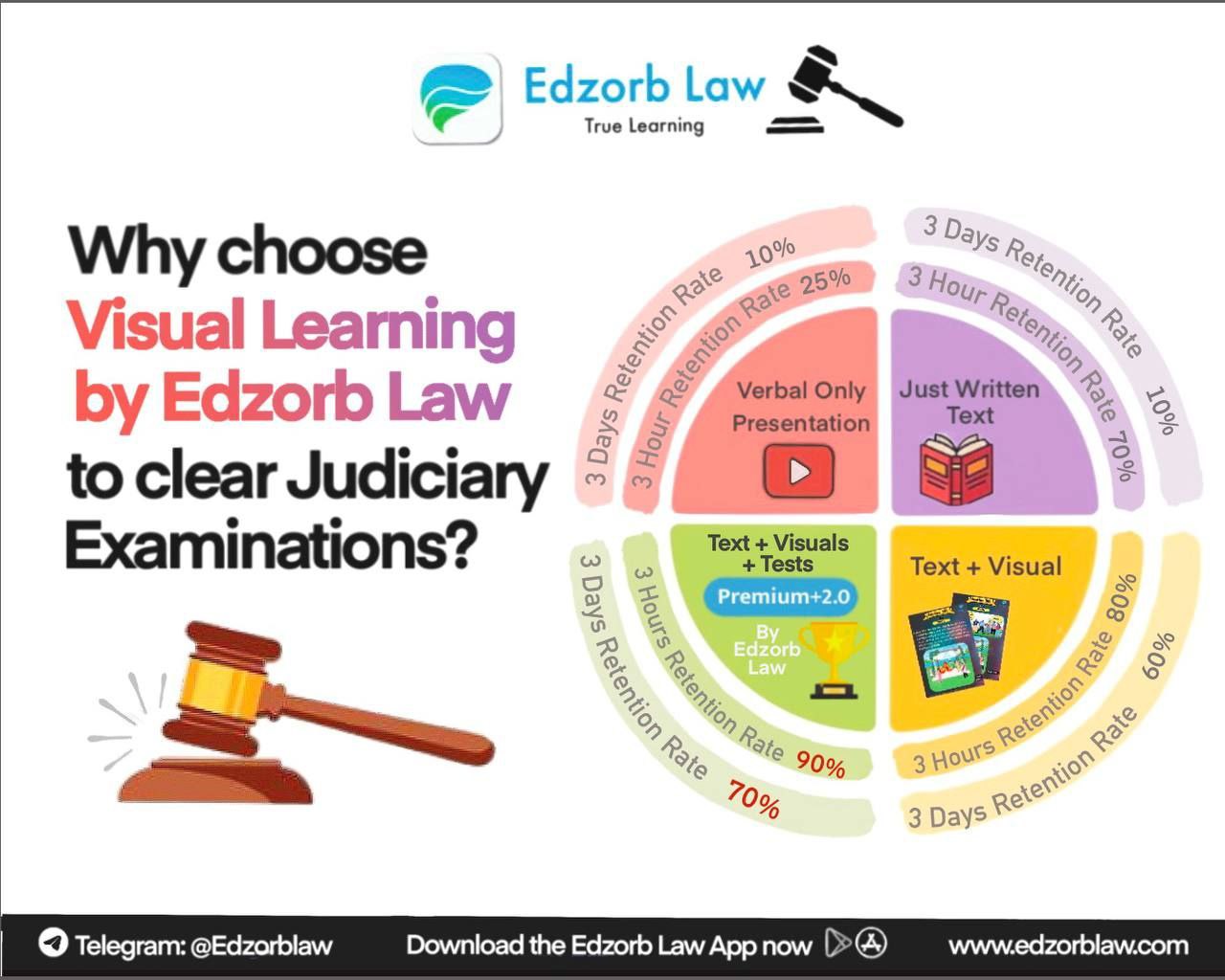

- Crisp notes, legal comparisons, and visual charts

- Memory hacks and concept-based learning

- Interactive modules, MCQs, and case law summaries

Don’t just read the law. Understand it. Apply it. Ace it.

🚀Downlaod Edzorb Law App and take the leap towards your judicial dreams!

Podcast

Podcast

Features

Features